An especially unpleasant form of gutter politics has infiltrated the 2024 presidential race as fellatio-obsessed right-wing provocateurs and the GOP nominee himself have sought to discredit Kamala Harris by making repeated (and repeatedly debunked) claims about her sex life.

If you’ve managed to avoid this corner of the political universe, you probably had a much more serene end to your summer than yours truly. However, as I’ll explain later, it’s important to pay attention to even the vilest attempts to sexualize women politicians, so here’s a quick primer:

Donald Trump and his allies are resurrecting an old and inaccurate line of attack by accusing Harris of leveraging a long-ago affair with a married man for political gain. Like many disinformation campaigns, it’s rooted in a nugget of truth. When Harris was an assistant district attorney in the early 1990s, she was romantically involved with a high-profile California politician named Willie Brown. He was still legally married at the time but had been estranged from his wife for a decade. Neither he nor Harris kept their relationship a secret. Brown supported one of Harris’s early local campaigns, but that was years after the two ended their relationship and part of his overall activism within the California Democratic Party.

During the 2020 presidential campaign, the right-wing media fixated on Harris and Brown. A paper I co-wrote a couple of years ago found that many of these stories included the phrase “Kamala the mattress” or “Willie Brown’s mattress.” Other research illustrates how this narrative, fueled largely by the hashtag #JoeandtheHoe, spread rapidly on social media, perpetuating damaging stereotypes about Black women’s hypersexuality.

A new — and somehow even more vulgar — version of this trope has emerged since Harris clinched the Democratic nomination. Shortly after President Biden ended his campaign, former Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly posted on X that Harris “actually did sleep her way into and upwards in California politics.”

Doctored images of Harris’s face superimposed on nude female bodies have been circulating online for weeks. Milo Yiannopoulos, a right-wing troll online and IRL, has taken to calling the sitting vice president “Cumala” and is headlining an event “roasting” Harris at the University of South Carolina later this month. (His co-host is Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes. Multiple groups, including the NAACP, are urging USC to cancel.) Trump, meanwhile, recently amplified a couple of lewd posts on Truth Social. One referenced parody song lyrics claiming Harris had “spent her whole damn life down on her knees.” The other was a photo of Harris with Hillary Clinton carrying the caption “funny how blowjobs impacted both their careers differently.”

Borrowing From an Old Playbook

The sexualization of women politicians dates back many decades and is especially intense when women seek high elected offices commonly associated with men and masculine traits. Shortly after Democrat Geraldine Ferraro became her party’s vice presidential nominee in 1984, a Denver Post columnist wrote that she “had nicer legs than any previous vice-presidential candidate” and speculated that she could be the first vice president to win a wet T-shirt contest. (Ferraro was also subjected to some pretty intense mommy shaming by Barbara Walters and treated by other journalists as a novelty rather than a serious contender.)

A modern mainstream news organization probably wouldn’t publish a column like the one that appeared in the Post back in 1984, but that doesn’t really matter. Our digital information ecosystem likely magnifies the impact of sexualized rhetoric. The 2008 election cycle is a good example. Social media was fairly new at the time, but it still fueled the spread of narratives about Sarah Palin and Hillary Clinton that branded them as subservient figures as opposed to potential political leaders.

After the GOP named Palin as its vice presidential nominee, the press obsessed over Palin’s time as a beauty pageant contestant and New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd infamously labeled her “Caribou Barbie.” Online, a micro economy of Palin-inspired merch and related memes proliferated, eventually including scantily clad action figures and an inflatable “love doll.” Her supporters branded her as a “MILF” and repeatedly shared a close up photo of her high heeled shoes.

Clinton, meanwhile, was mocked for her perceived lack of sex appeal. Several popular Facebook groups emerged where members chastised Clinton for her pantsuits and refusal to conform to traditional gender roles. They attracted tens of thousands of followers and had names like “Hillary Clinton: Stop Running for President and Make Me a Sandwich,” “Life’s a Bitch, Why Not Vote for One? Anti-Hillary ’08” and “Hillary Clinton Shouldn’t Run for President, She Should Just Run the Dishes.” These groups were, for the most part, created by young, very online men and portend the kind of toxic masculinity that pervades the far right today.

The 2016 election cycle subjected Clinton to another round of sexualized attacks including repeated vandalization of her Wikipedia page with pornographic images and a set of memes featuring a KFC-style takeout bucket with the slogan, “Hillary Meal Deal: 2 Fat Thighs, 2 Small Breasts, and a Bunch of Left Wings.”

This misogynistic through line from 1984 to now is more than just rude, gross and demoralizing. Pervasive sexualized rhetoric objectifies women politicians by reducing them to their physical traits. It also disempowers them by linking them to specific men or, more generally, the male gaze. A growing body of research shows that this type of objectification reduces a woman candidate’s chances of success. It also has damaging effects on women voters who internalize these sexist messages and, in ways both subtle and overt, become less likely to challenge traditional gender roles at the ballot box and beyond. It is, as researcher Claire Gothreau writes in this essay for the Center for American Women and Politics, “an oversight to discuss sexism in politics without talking about objectification.”

There is, however, some hope. It’s likely impossible to stop digital slut shaming of powerful women, but drawing attention to sexualized attacks can, as Gothreau puts it, “disrupt the objectification loop.”

These types of call outs have become more common in the last few years among activists and political journalists. While the New York Times of 2008 treated the sexy Palin action figures as an Internet joke, the modern Times did a pretty good job of documenting Trump’s sexist Truth Social posts and juxtaposing them with his own history of mistreating women. There are plenty of other good examples, too, like this combination call-out/fact check from Newsweek and this MSNBC piece that frames the attacks on Harris as part of broader misogynistic currents within the GOP.

Covering references to blowjobs and political sex toys can be cringy — this essay has been giving me heartburn for the better part of a week — but it’s a necessary part of responsible journalism, especially as the political arena becomes more diverse. As history has shown, ignoring this problem won’t make it go away.

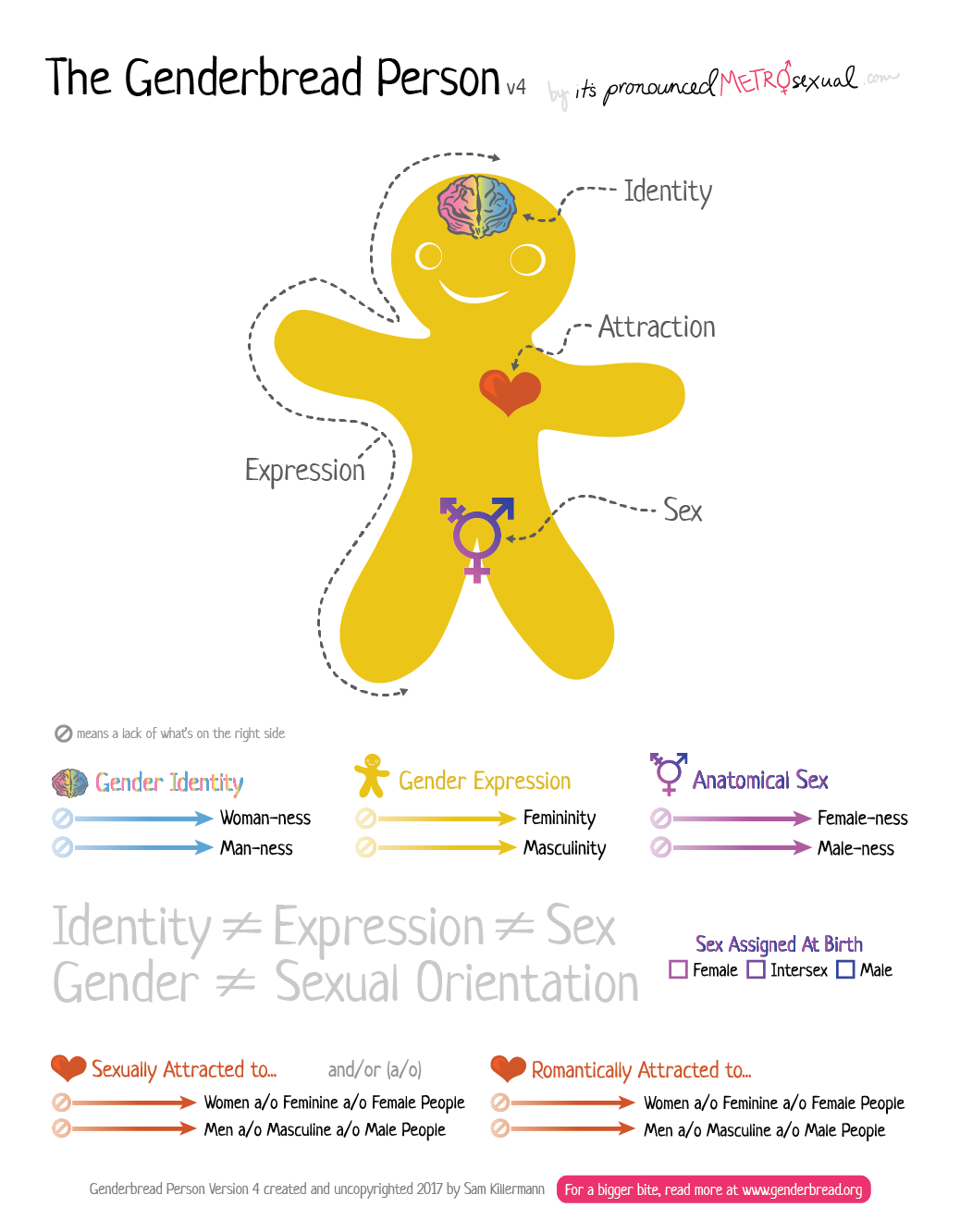

What we talk about when we talk about gender

It’s back to school season, which means I’m deep in the weeds of planning a course I teach called Gender in the Newsroom. Talking about gender can be confusing, so I’ll be sharing this lighthearted-but-useful graphic with my students next week. I thought you might enjoy it, too.

🎩 h/t to the brilliant Dr. Chelsea Reynolds for putting this (and the related Gender Unicorn) on my radar a few years ago. They’re such helpful resources!